Hello, everyone!

Today, we would like to share with you our approach to creating missions. We’ll tell you why the production takes so long, what importance there is to the story, and give you the broad strokes of the creation stages.

At the time of writing, there are 12 missions to complete in Caliber. Four of them have been completely reworked and received cutscenes, new segments and improvements: Al-Rabad, Palm Road, Caravanserai and Prologue.

Each mission is a result of meticulous, step-by-step work by a large team. There are many people involved in production: mission designers, programmers, concept artists, 3D modelers, animators, environment artists, visual effects designers, sound designers, video production department, testing department, narrative designers, and UX/UI designers.

At the start of development, the responsible staff member has the info on the map and story. This is enough material to be able to answer: «What are the operators doing here?»

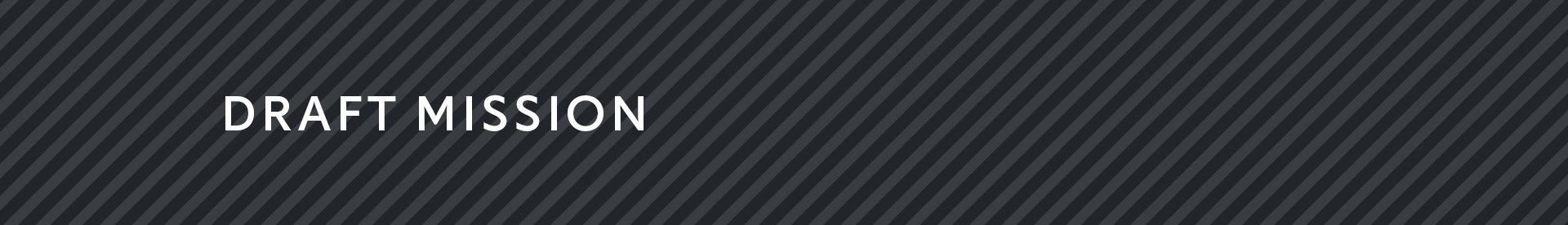

The answer to this question allows us to finalize where the point of interest for players should be placed. Then, the mission designer starts to develop the players’ potential routes for the map.

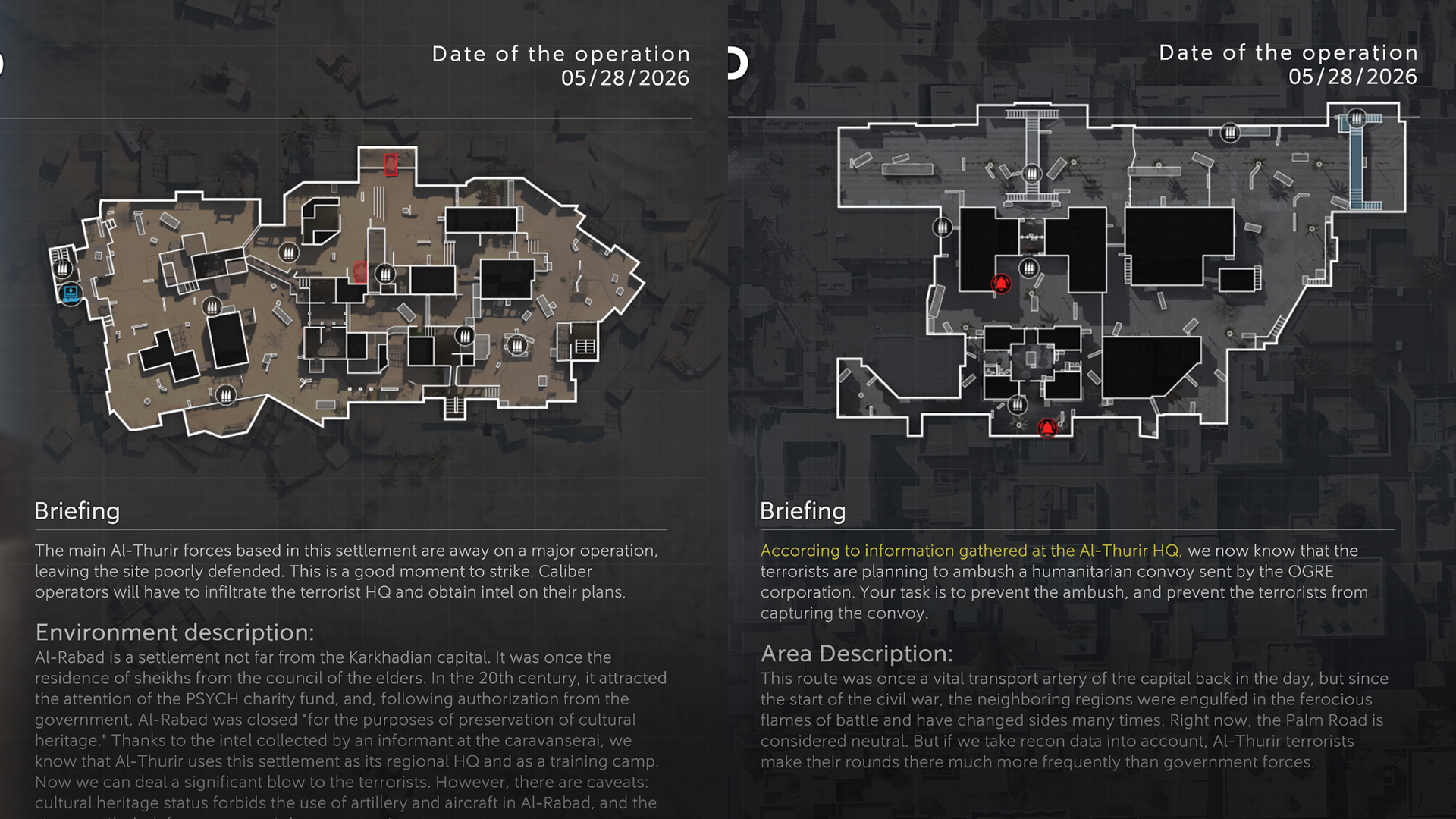

Let’s look at the new mission for Palm Road, for example. The story is predetermined — the operators are to intercept an ambush on a humanitarian aid convoy.

That means the ambush will take place on the road, and the final point of interest is known. Also, the ambush of the Al-Thurir militants means that our operators have to act in secret. The route for players is set through dark alleys. The new bot alarm mechanic is added as well.

The story determines the possible actions and goals of the players.

After preparing the route, the mission is then divided into segments that have the events written for them: the cutscene, the shootout, resting and ammo replenishment, the dialogue, device interaction and so on.

All info about the story, route, mission segments and possible dialogue script are put into the draft of the design document for all involved in the production to refer to at any time.

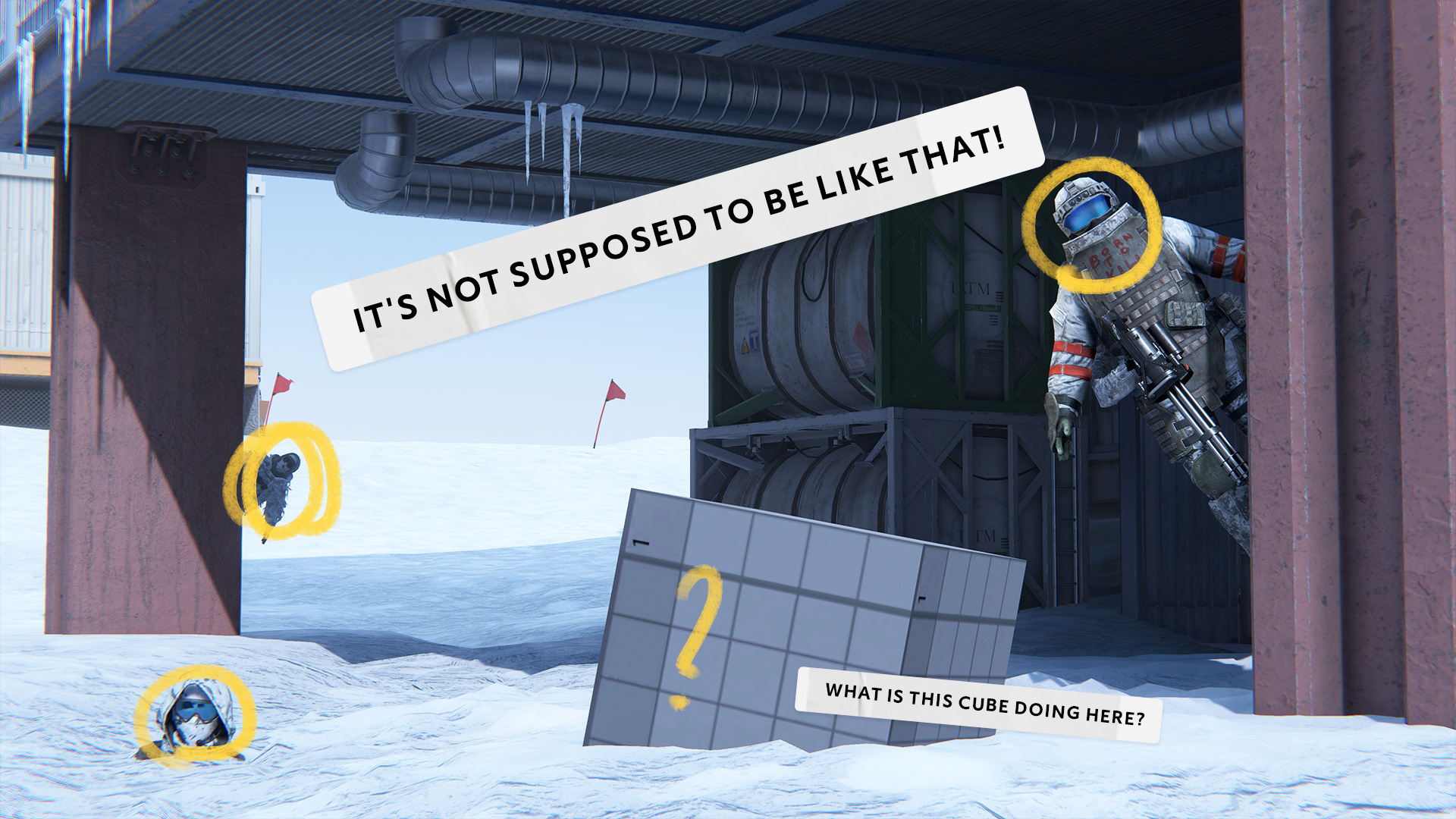

The draft mission is created on the basis of the draft design document. At this stage, the mission designer constructs the mission’s basic logic so that it would be possible to complete it. A basic cube rides upon the roads instead of a car, the dialogues are not voiced, the buttons are simplistic geometric shapes, etc.

The mission is configured in such a way that makes it possible to start testing and to understand how engaging it is from a gameplay standpoint.

The following steps are needed to create a mission:

1. Customizing bots.

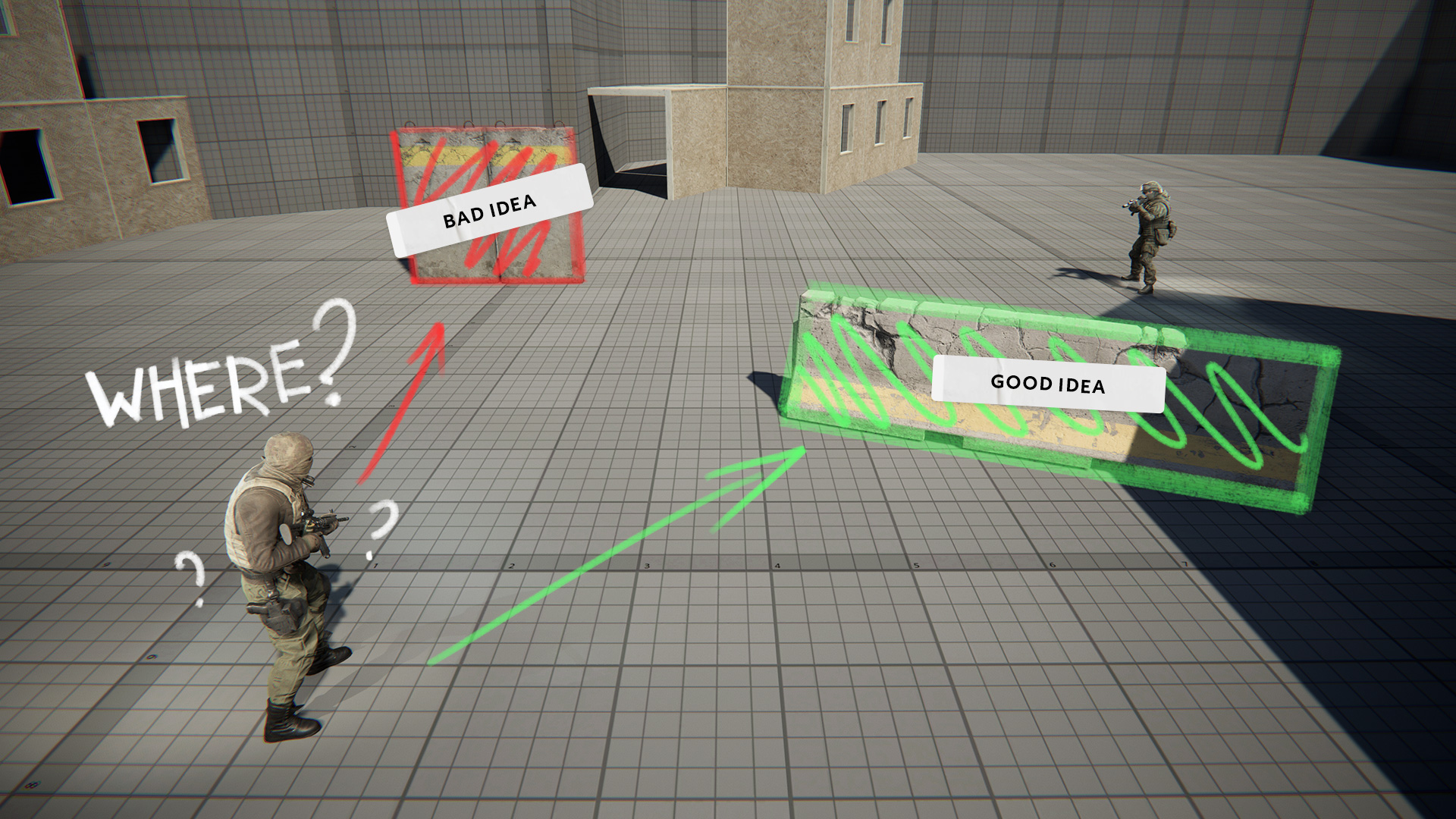

The mission designer has to answer several questions before filling the map with bots: Who? Where from? Where to? When and how many?

The gameplay experience that the player receives here is directly influenced by these answers.

Customizing the bots is the most labor-intensive and time-consuming task when creating a mission. Shootouts with bots should pose a challenge, but not to the point that they are impossible to beat. This requires making changes after almost every play test.

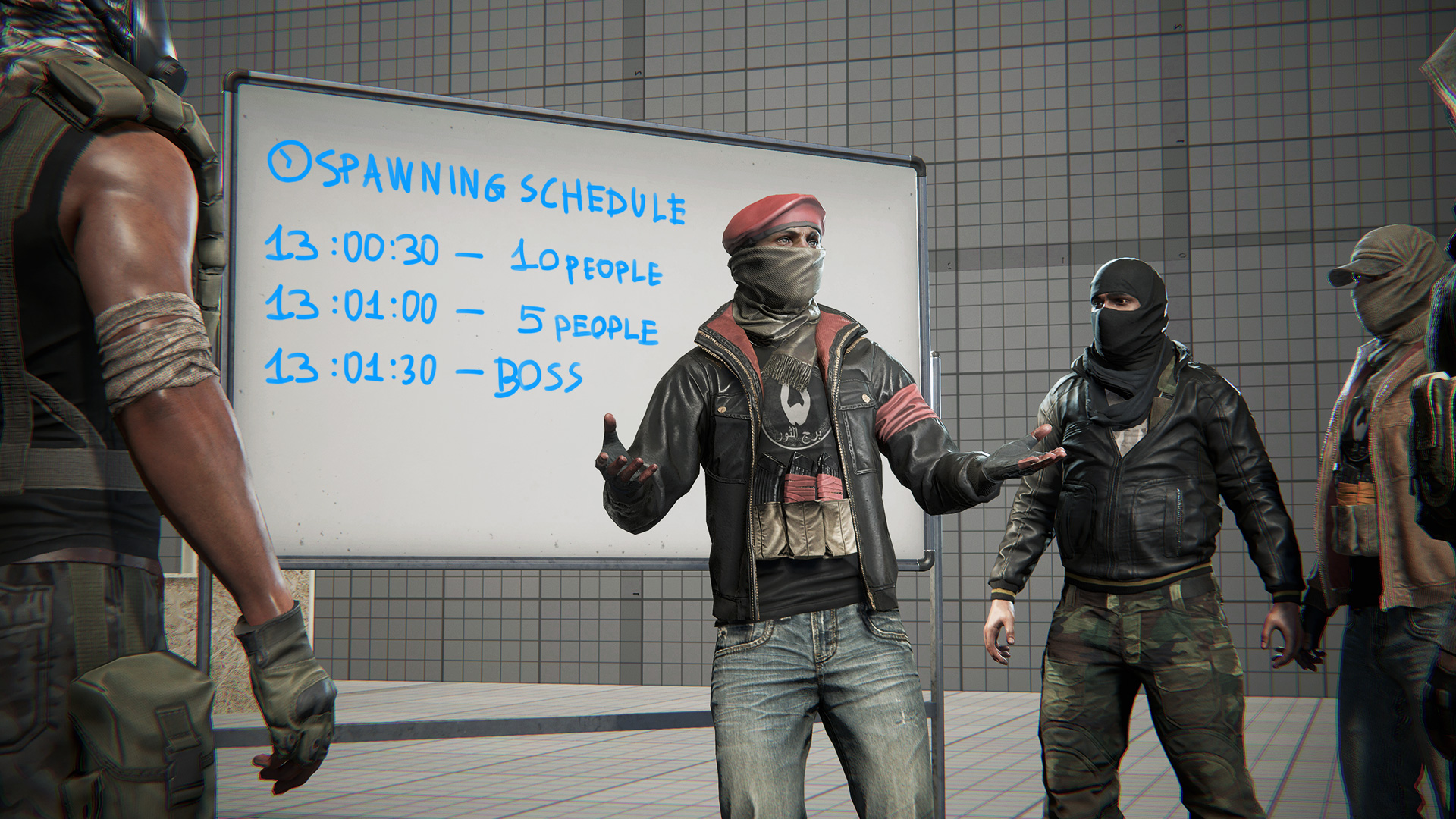

2. Setting the triggers for starting each segment.

This involves much less time compared to the bots. But one broken trigger is enough to render the mission impossible to beat.

3. Placing covers.

4. Placing ammo crates.

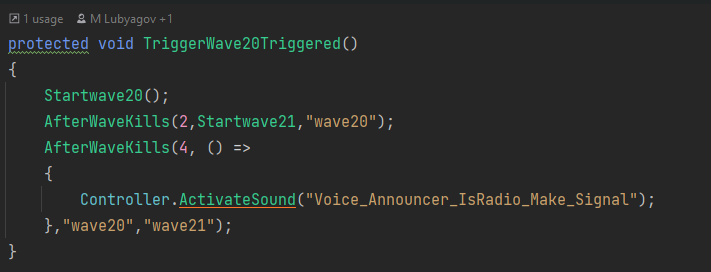

5. Working with the scripts.

So, the draft mission is complete. There is a beginning, midpoint and end to it. The testing may begin now.

Testing is done by the company’s employees and Polygon combatants. We play the mission while noting down any errors and our own impressions. The mission designer analyzes the information and then makes changes based on the feedback given.

Rinse and repeat. Many, many times.

The main goal of draft mission testing is to check the map’s geometry and various assumptions to understand whether an idea that sounded good on paper feels just as good during actual gameplay. If the map does not meet our expectations, then we go back to rework the idea and correct the design document.

A mission can change drastically during the many phases of playtesting. But in the end, we get the finished design document.

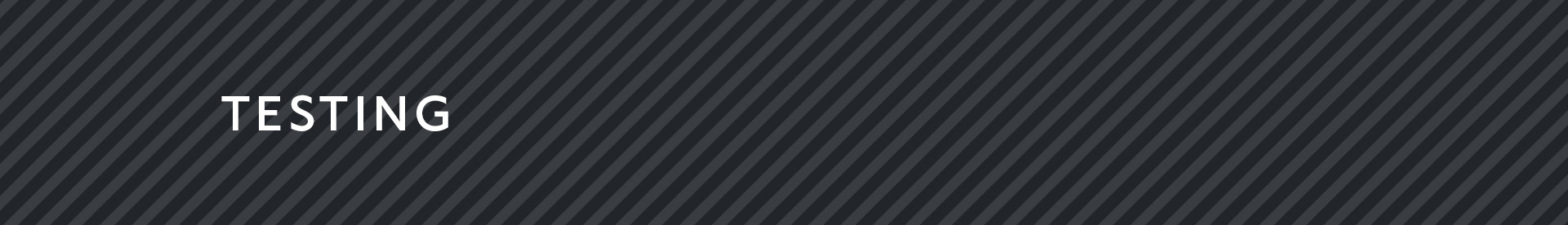

The final design document contains all the tasks required to finish creating the mission. It serves as the guiding text for the employees who will work on the sound and visual effects, change the map geometry to better serve the mission’s needs, voice the dialogues and much more.

The process of creating elements to fill up the mission starts at this point.

If the previous stage came and went in quick succession, element production for filling up the mission happens concurrently.

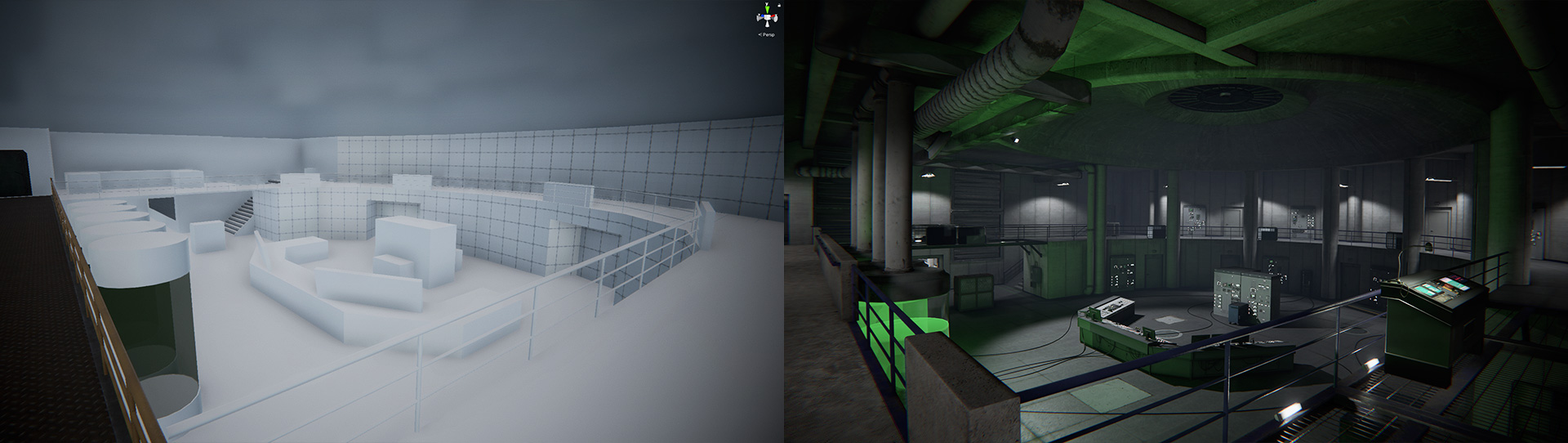

To create a mission, it is sometimes necessary to rework the map, and sometimes the creation of an entirely new location is in order. This is exactly what happened with the Forest map missions.

During the development of the mission, a decision to add a bunker for the mission’s boss character, Isaac Delgado, was made. We started work on the concept and geometry of the bunker.

A new phase of testing begins when the concept for any location is complete. Our team plays through the mission on a map filled with gray cubes and surfaces, and tries to determine how fun it is to play on.

If everybody enjoys the map, we begin the process of creating the 3D models for the «playset». The environment designers then use those models to make the location presentable for the players.

If a mission needs a new bot, it will have to be created from scratch as well. Creating concepts, creating a 3D model, preparing and applying textures, animating.

When these steps are done, the bot still has to be customized.

The new visual effects are created specifically for the new missions. Even a simple explosion is different: you cannot just go and reuse an already-made car explosion to display a barrel igniting.

The gas was created specifically for the Forest mission, the tire tracks for Palm Road, the Shilka firing and various explosions for Al-Rabad.

We use mocap to create the animations, such as the bots’ movements and operators interacting with objects.

After recording the animations during a mocap session, the mission designer then picks the best ones, uploads them to the game engine and adds them to the project. The animations are considered «rough» at this time.

The rough animation is in an unfinished state: the movements are unnatural and look vastly different from the finished versions that we are used to seeing in-game. The animators will have to clean them up by meticulously fine-tuning each and every movement. In spite of this, mocap animations are a huge time saver.

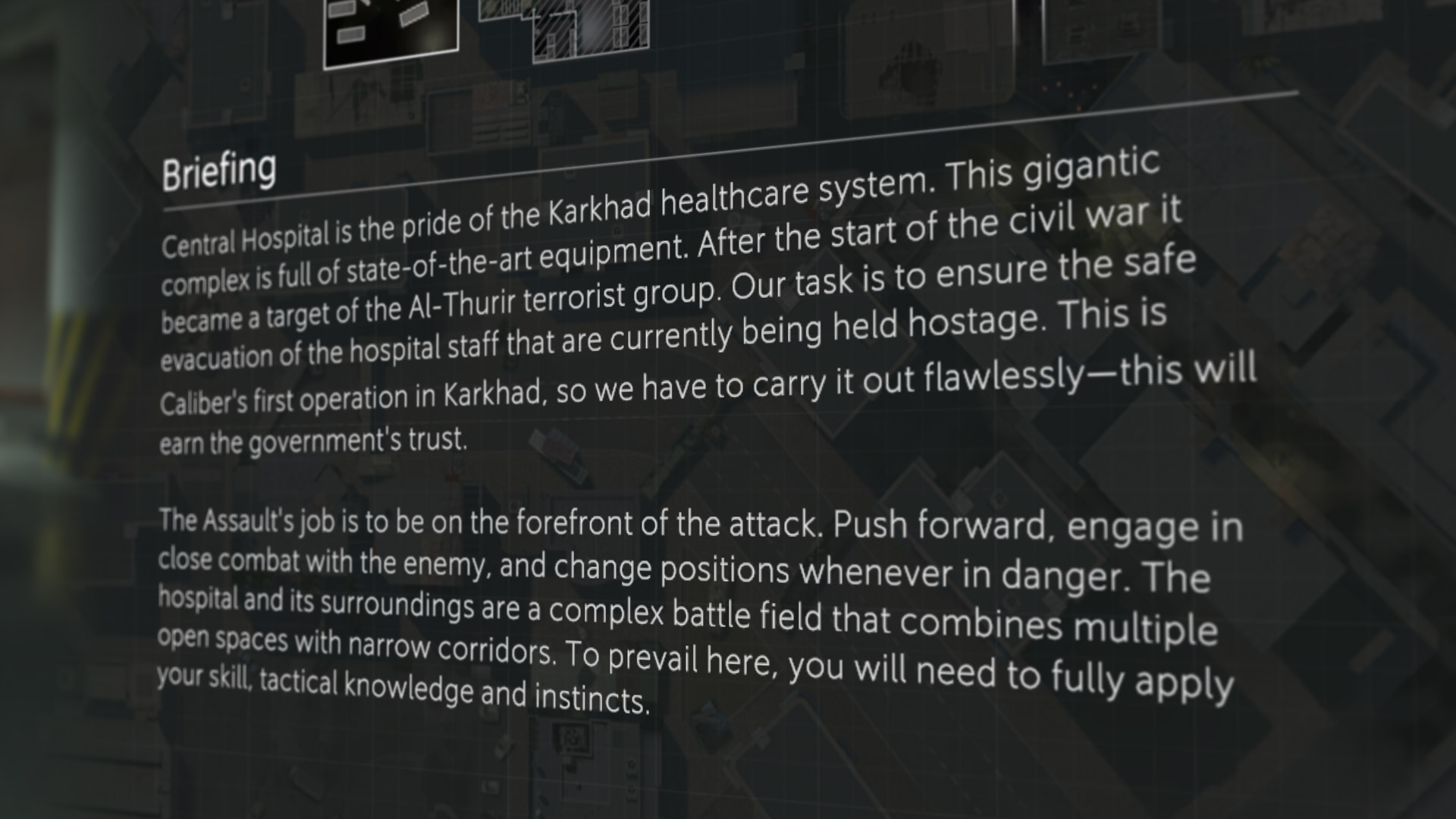

The narrative designer writes the location description, the mission briefing and the dialogues that you hear during gameplay. At the very beginning, the story is just a simple outline. The narrative designer adds the details near the mission’s completion.

The mission designer comes up with gameplay situations, and the narrative designer makes them work in regard to the pre-existing story and lore, as well as to common sense.

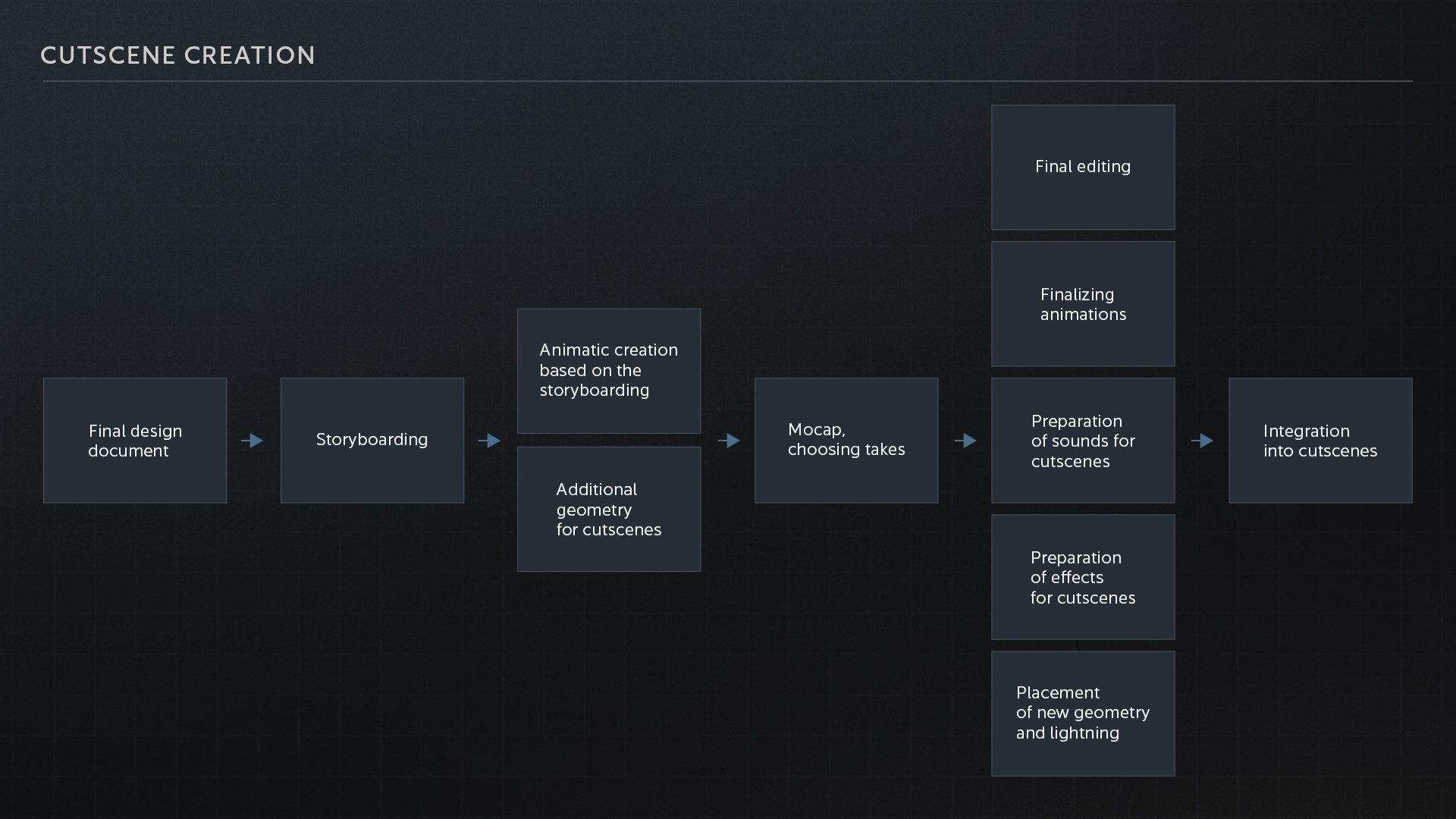

The mocap studio and new video production department allowed us to start creating full-fledged cutscenes for the start and end of missions. Just as with the rest of the team, the video production department is an entire enterprise that we only mention here in a specific context.

Everything starts at storyboarding, which is done according to the final design document. This allows us to see a snapshot of the future cutscene, and to determine what exactly will be in the shot, which animations to record, and what to accentuate.

We place the cameras and objects on the desired positions, then film the animatic based on the storyboard.

An animatic is an in-engine cutscene based on the storyboard. It does not have any animations, sounds or effects at first. This allows us to evaluate the selected camera angles, the composition, the frame rate, etc.

After the animatic is approved, a list of animations is then created and sent to the mocap studio for recording.

The map geometry often ends up being reworked specifically for the cutscenes. It is made with aesthetics in mind, regardless of whether it is going to be used during gameplay.

Mocap has been mentioned before, but the amount of their work is tenfold for cutscene creation alone. Cutscenes often use unique, single-use animations.

At this point, the video designer can use the rough animations to create the first draft of a cutscene. Since it is shot in-game, those draft animations can easily be replaced with their final versions. They will be played at the required place, at the required time.

Polishing can also be done at this stage, such as moving the cameras around, changing the timing for selected scenes, and so on.

The animators then refine the materials received after mocap recording. The level designers place the final objects and light sources at their designated spots on the map.

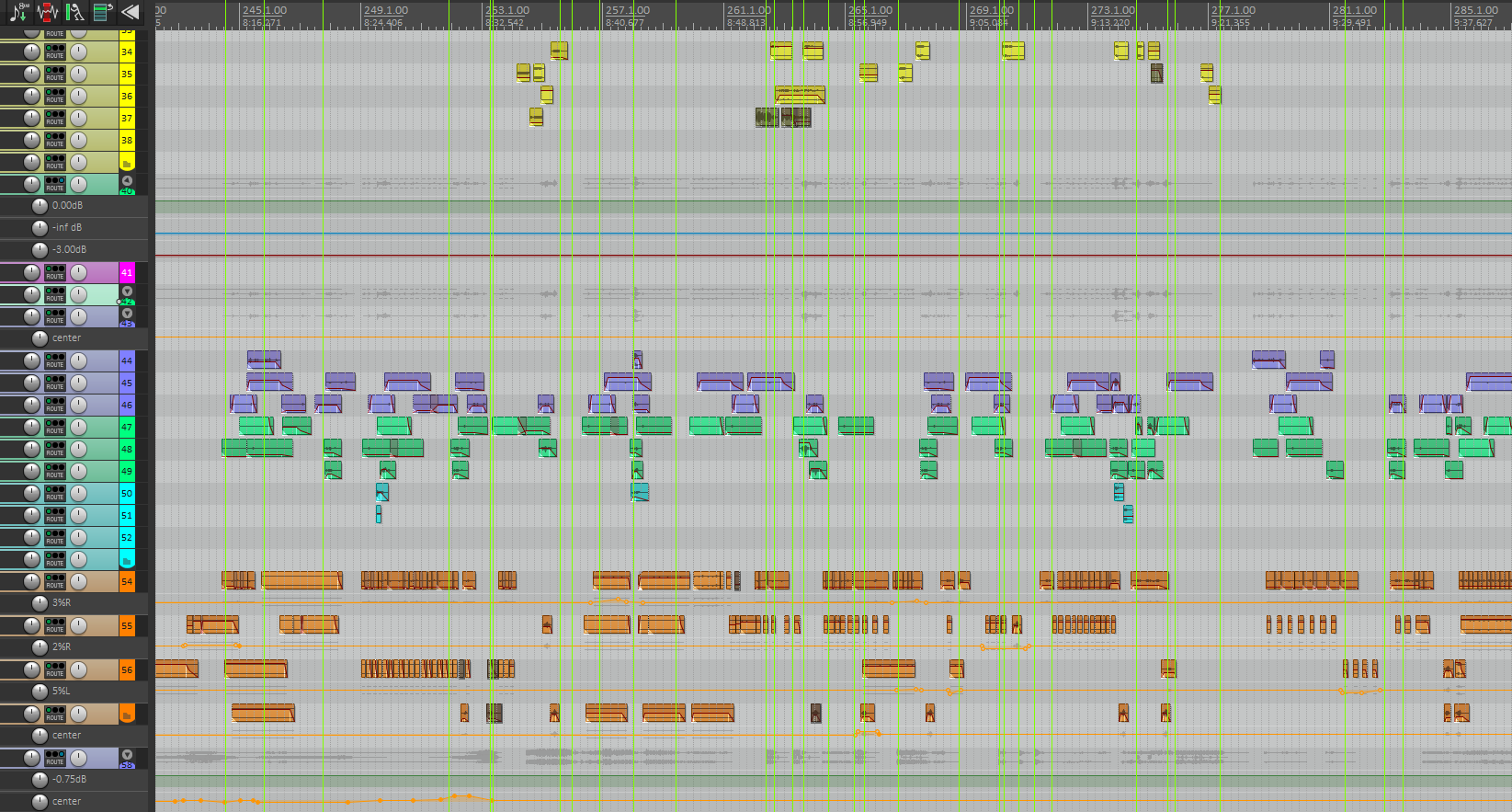

When the film director and video designer decide on the length of the cutscene, the visual and sound effects specialists get to work. They can roughly estimate what would look and sound nice beforehand, but start working in full only after the exact length of the cutscene — down to the millisecond — is determined. This is because if you cut out even a tiny fraction of the video, the effects will play at the wrong times, and the sound will lag behind.

This image features sounds of operators and bots from a Prologue cutscene: voices, footsteps, and clothes rustling.

Integration of cutscenes is done before they are fully completed, since it will have to be tested just like the mission itself. The cutscene is not a pre-recorded video, but a sequence that runs on the game engine. It can look different depending on the settings.

While other departments were creating the assets to fill up the mission, the mission designer was busy polishing the bots, fine-tuning the events (creating scripts, working with the configs) for the different segments of the mission, plugging in the dialogues, creating object markers and organizing yet another playtesting session.

After all the departments have finished and turned in their work, the mission designer links everything up and conducts the final play test while ironing out any last errors and bugs.

Then, the finished mission is distributed to all players on the day of the update. Hooray!

But this does not mean that work on the mission is over yet.

A bug that needs to be fixed can be found in any mission at any time. Even something that worked fine before can break down. Just because there were some alterations made to the project.

Here is an abstract example: a new tool for customizing the bots gets integrated into the project. It allows for more flexible customization of the AI-controlled characters, but this means that all the bots, across all the missions, will have to be fine-tuned once again.

Global changes can influence many parts of the project.

That’s why you can still see bug fixes for old missions. The work on missions never ends, even if they have been released for a long time.

We create separate missions for some events, which are available for a limited time only. There are three of these missions so far. Two of them were created in celebration of Victory day: "Defense" and "Storm". And the last one, dedicated to Halloween: "Onslaught: Halloween."

The creation of such missions always implies reworking the maps, the bots’ models and various tiny details of the environment, the production of unique effects, sounds and everything else that we have mentioned above.

Even though the missions are time-limited, the production costs are still the same, if not higher.

To create just one mission requires involving more than ten of the company's production departments, a lot of testing and fine-tuning, and implementing constant support.

We continue to develop and hone our skills so that we can implement more new mechanics going forward, to deepen the lore, and improve the flow and presentation of the story. We will always prioritize the quality of our missions over quantity.

Right now, a new mission is in development for a map that has never had one. We will share details when it is ready for presentation.

This article is the tip of the iceberg. We would need much more space to reveal all the nuances of each department and show their step-by-step workflows. Whether or not those articles will be written depends on your interest.

Thank you all for reading!

WHY DOES CALIBER NEED A STORY?

The story is something that makes the project engaging and entertaining. It helps to involve the players in the game more, and to give motivation to their actions. In other words, the players should understand the world they are in, what they are doing, and to what end. This makes the game more interesting.

It is especially important for PvE modes. If the main goal in PvP modes is to fight other players, then in PvE it is to fight with bots. So, it is of the utmost importance that the players understand exactly who they are opposing. Fighting a bunch of pixels is rather dull, compared to the Al-Thurir terrorists. This is why Caliber has a story mode.

Even though players complete the missions in a random order, all of them have an overarching plot that forms a complete picture when pieced together.

The films of famous director Christopher Nolan sometimes show events in a surprising order. The same is true for our game.

WHO DECIDES WHAT HAPPENS IN THE CUTSCENES?

The scenarios for the cutscenes are written by the narrative designer, the video production department and the mission designer. And of course, everything that happens in the cutscenes has to follow the mission storyline and pre-established lore.

WHY ARE THE MISSIONS RELEASED LATER THAN THE MAPS THEMSELVES?

In a nutshell, this article is your answer. Many staff members have to be involved in development, and the testing is also done in-house.

The PvP-modes, which see new maps become available almost instantly, need the help of far fewer departments. It is impossible to completely balance a PvP map using only in-house testing. We release a new battle-ready map, then continue to make balance improvements according to the players’ experience.

HOW HARD IS IT TO CREATE NEW MECHANICS FOR MISSIONS?

It depends on the mechanic.

For example, it was relatively easy to create the bots’ alarm tracking for Palm Road, or the Delgado fight for the Forest, as those mechanics have only been used in two missions. But if there is a mechanic that concerns all bots, it will have to be implemented for every single mission.

WOULD THERE BE MORE MISSIONS IF THERE WERE MORE MISSION DESIGNERS?

No. There would be more draft missions, which would be placed in the queue for playtesting, then there would be a long wait for all the assets for filling up the map to be created by the other departments.

WHY ARE THERE SO MANY/FEW BOTS?

At the moment, the game has a technical limitation: no more than 20 characters for any given gameplay scene. Depending on the mode, four (the missions and Onslaught mode) or eight (Frontline and Threshold) are reserved for the players, and the rest of the slots are filled by the bots. Until a bot is eliminated and removed from the map, a new one will not be able to appear.

We think there are enough bots, seeing as Caliber’s maps are pretty compact in size, so every player has enough targets to keep them busy.